Study exposes dangers of too much fluoride, says children are at INCREASED risk of tooth decay from using too much toothpaste

05/17/2019 / By Tracey Watson

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) calls the process of adding fluoride to drinking water to improve dental health “one of the ten most important public health advances of the 20th century,” claiming that it significantly decreases rates of dental decay. Water fluoridation has been the official government policy of the United States for many decades now, and over 64 percent of American citizens drink fluoridated water every day.

In addition to drinking water, health officials also recommend that fluoride be added to most toothpastes, including those designed specifically for use by children.

Has all this fluoride fulfilled its promise of improved dental health? Actually, studies have found a marked increase in the number of people diagnosed with fluorosis in recent decades. Fluorosis is a condition caused by excessive intake of fluorine compounds which causes stained, mottled teeth, and in severe cases, can result in calcification of the ligaments.

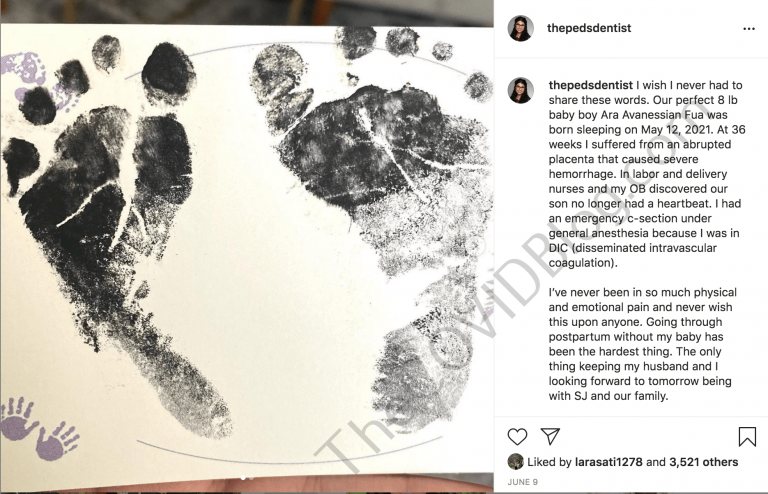

As reported by the U.K.’s Daily Mail, one possible reason for this disturbing increase is that according to a survey conducted by the CDC, almost half of all children – 40 percent – use far too much toothpaste, which instead of promoting dental health can result in dental fluorosis. (Related: Is severe dental fluorosis an adverse health effect?)

What the survey determined

Even though health officials insist that the benefits of adding fluoride to toothpaste outweigh the risks, they do recognize the need to use exactly the right amount. Toddlers under the age of three are supposed to use a minuscule smear no bigger than a grain of rice, while kids between three and six are supposed to use just a pea-sized amount.

The CDC’s survey, which included 5,000 children between the ages of three and 15, found that most kids use far more toothpaste than the recommended amount, likely because child-specific toothpastes are generally made to taste sweet.

The Mail reported:

‘Fluoride is a wonderful benefit but it needs to be used carefully,’ said Dr. Mary Hayes, a pediatric dentist in Chicago.

Young kids may push for independence in brushing their teeth, but kids’ toothpaste tastes sweet.

‘You don’t want them eating it like food,’ Hayes said. ‘We want the parent to be in charge of the toothbrush and the toothpaste.’ …

The study found about 60 percent of kids brushed their teeth twice a day. It also found that roughly 20 percent of white and black kids, and 30 percent of Hispanic kids, didn’t start brushing until they were three or older.

Why fluoridation is NOT an important public health advancement

While a very specific amount of fluoride added to drinking water and consumed at just the right doses appeared to improve dental health in scientific studies conducted nearly 100 years ago, the reality is that most of us are consuming far too much of it, resulting in a dramatically increased risk of dental fluorosis. Natural News previously reported:

Data collated by the World Health Organization found no difference in tooth decay numbers, when countries with fluoridated water supplies were compared with those that did not add fluoride to theirs. Other studies found that, in fact, cities with fluoridated water had higher cavity rates than non fluoridated cities. This result was attributed to a condition known as dental fluorosis, where fluoride actually weakens and eventually damages the tooth enamel.

Fluoride accumulation in bones has also been found to make bones brittle and more susceptible to fractures.

So, not only does adding fluoride to drinking water and toothpaste increase the risk of fluorosis, but it likely doesn’t even reduce the risk of tooth decay.

Fortunately, fluoride-free children’s toothpastes are available, and water filters like the Big Berkey are capable of reducing levels of this dangerous toxin in drinking water. Learn more at Dentistry.news or Fluoride.news.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

cavities, children's health, Dental fluorosis, dental health, dentistry, drinking water, Fluoride, fluorosis, oral hygiene, parenting, poison, products, toothpaste, toxins

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author